What China’s growing involvement means for Myanmar’s conflict

A diplomatic intervention by China is propping up the junta in Myanmar by pushing the country’s strongest ethnic armies to limit their support for the post-coup uprising. By helping to slow the evolution of the resistance movement, China may ensure the longer-term survival of the Myanmar junta.

Graphics by Brody Smith

Edited by Aaron Connelly

In December 2022, China’s new special envoy for Myanmar, Deng Xijun, held his first meetings with seven of Myanmar’s most powerful ethnic armed organisations (EAOs). During a series of subsequent discussions, Deng expressed two policy positions. Firstly, that China would more actively enforce its policy against instability along the border. Secondly, that the EAOs should distance themselves from the National Unity Government (NUG), an opposition body established by lawmakers ousted by the coup, because the NUG had grown too close to the West.

Since late 2022, Chinese diplomats have become increasingly active on Myanmar, using their influence to facilitate face-to-face meetings between the regime and members of a loose alliance known as the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). While this intervention is unlikely to achieve a political solution or an end to the violence, it carries fundamental implications for the continuing conflict between the junta and other, newer opposition forces that are seeking military and political backing from the FPNCC groups. By coaxing key EAOs to forego military action and limit any support for the NUG and its People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), China is helping the regime achieve its key strategic objectives.

Old and new threats

Over the last two years, the Myanmar junta has faced two broad forms of armed opposition. The first is a continuation of a decades-old pattern emanating from the country’s peripheries where an assortment of longstanding EAOs operate. Following the 2021 coup and the effective collapse of the country’s peace process, several important EAOs chose to renew their armed struggle against the military. Other EAOs have remained on the sidelines, refusing to endorse the coup but at the same time standing aloof from the resistance to it.

A second, newer axis of resistance has emerged in the form of a grassroots uprising primarily among the Bamar ethnic majority. In response to the regime’s violent crackdown on anti-coup protests in early 2021, civilians across the country organised themselves into local resistance groups generally referred to as PDFs. Many of these units later declared broad political association with the NUG, though on the ground most continue to operate either independently or under the command of EAOs. The highest concentration of active PDFs is found across Myanmar’s Dry Zone, the heartland of the Bamar majority.

Despite facing a sharp rise in PDF attacks, the regime has continued to view the EAOs as its greatest military challenge.

Despite facing a sharp rise in PDF attacks, the regime has continued to view the EAOs as its greatest military challenge. With decades of fighting experience, direct access to weapons markets, and consolidated command structures, EAOs possess the means to seriously contest the junta’s entrenched positions and strategic interests. Given their capabilities, open combat with the EAOs requires of the junta a considerable expenditure of resources, a challenge for an embattled military now stretched across multiple fronts.

In contrast with some EAOs, most PDF units continue to lack the needed firepower or command and control to capture well-defended positions. While some units have grown adept at roadside ambush and, through campaigns of targeted assassination, proven able to disrupt aspects of the regime’s civil administration, individual PDFs in the Dry Zone pose less threat to the regime’s grip on strategic assets, such as highways, airports, major bases, and towns. Moreover, the regime’s superior firepower means that it can insert itself deep into territory where PDFs operate, making it impossible for poorly equipped units to maintain a frontline or establish meaningful control over areas where the regime’s administration has been weakened.

The regime’s post-coup strategy

In a clear reflection of its threat perception, the junta has dedicated relatively few resources to combating the PDFs, relying primarily on punitive scorched-earth tactics carried out by local village militias and a small number of soldiers instead. At any given time since the coup, no more than three outside divisions have been deployed to cover the vast expanse of the Dry Zone, the epicentre of PDF resistance. Instead, the bulk of the military’s mobile strike forces — comprising 10 light infantry divisions and 20 division-level military operations commands — has remained in place to deter EAO offensives in the peripheries, with many units seeing no combat at all. In Rakhine and parts of the northeast, this strategy has largely succeeded, helping to ensure the general continuity of delicate ceasefires with several key groups.

In areas like the northwest and southeast, however, the regime’s strike forces have failed to deter the EAOs. Following the coup, some brigades from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and Karen National Union (KNU), for example, launched direct offensives on regime positions. They also facilitated the rapid transformation of nascent PDFs through the provision of training and arms, and by accompanying inexperienced fighters during ambushes and attacks. With few exceptions, newer PDF units have managed to overrun police stations and a limited number of remote military outposts only when led by EAO commanders. So far, the most capable PDF units are those which have received direct support and leadership from the EAOs.

It is at this nexus — the fusing of grassroots armed resistance and EAO activities — where the greatest potential threat to the regime lies.

The advent of the popular armed uprising has allowed some EAOs to increase their strength and capacities by co-opting new PDFs and using these units to expand their areas of influence. Some PDF fighters trained by the EAOs have also returned to their villages or cities to establish new resistance groups. EAOs have sold limited quantities of weapons to some of these outfits, including ones that are closely aligned with the NUG. It is at this nexus — the fusing of grassroots armed resistance and EAO activities — where the greatest potential threat to the regime lies.

Recognising these challenges, the regime has held two primary aims. Firstly, it has worked to break new partnerships by punishing the leaders of EAOs who support PDFs and sparing those that do not. This effort has entailed the more aggressive use of airpower, with airstrikes on sensitive EAO leadership assets that were previously deemed off-limits by both sides. In October 2022, for example, an airstrike on a concert killed the commander of the KIA’s 9th Brigade. A month later, the regime’s aircraft targeted the headquarters of the KIA’s 8th Brigade. These attacks appeared to produce some effect. In November 2022, the KIA halted its offensive activities in Kachin for the first time since the coup. Fighting was reduced to limited clashes near the state’s resource-extraction points until the junta launched a renewed offensive near Laiza, the KIA’s nominal headquarters, in early July 2023.

Secondly, where EAOs have not overtly supported new PDFs, the regime has offered dialogue and concessions as a way to shore up existing ceasefires and prevent the transfer of weapons to PDF units. Rather than attempt to stamp out PDFs as soon as possible, the junta has primarily focused on stunting the movement’s evolution, thereby extending the window of opportunity to bargain with the EAOs. By seeking a deal with its key opponents, especially those within the FPNCC, the junta hopes to free up its mobile strike forces deployed in the peripheries so that it can redirect them against hotspots of PDF resistance. On the whole, the junta aims to compartmentalise the conflict, dealing with threats individually rather than all at once.

The FPNCC

Since the coup, the junta has faced an axis of resistance stretching from Myanmar’s southeast, to the central Dry Zone, and up to the northwest. By contrast, FPNCC groups operate primarily in the northeast and Rakhine state. A decision by a majority of FPNCC groups to wage direct offensives in their areas would force the junta into major combat operations along two primary axes at once. Given both this scenario and its position as the largest potential source of weapons for the PDFs, the FPNCC could alter the trajectory of Myanmar’s post-coup conflict. For this reason, securing the neutrality of the FPNCC groups through a negotiated bargain has been a paramount objective for the regime since it seized power in February 2021.

Formed in 2017, the FPNCC is led by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), a group that maintains close ties with the Chinese Communist Party. The UWSA controls a de facto statelet, divided into two non-contiguous territories along the Chinese and Thai borders. Wa leaders command an estimated 25,000 troops equipped with weapons originating from China, including FN-6 Man-Portable Air Defence Systems, armoured vehicles and various light weapons. The UWSA also assembles a version of the Chinese Type-81 automatic rifle at a factory in its area of control. While China has historically limited the Wa from transferring more-capable weapons to other actors in Myanmar, the UWSA has become the principal source of small arms and light weapons for its FPNCC allies.

The UWSA is also close with the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) and the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP). Both the UWSA and NDAA are direct offshoots of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), a former armed group which split up amidst a mutiny in March 1989, while some SSPP leaders are former party members. All three groups maintain stable ceasefires with the Myanmar military, agreed to shortly after the CPB’s collapse. The NDAA and SSPP typically follow the UWSA’s lead, especially when it comes to dealing with the Myanmar military.

Given both their close relations with China and longstanding agreements with the military, the UWSA, NDAA and SSPP are all unlikely to seek a renewal of direct confrontation with the regime. However, the chaos of the post-coup order has created an opportunity for these groups to expand their influence by supporting other EAOs whose ceasefires with the regime are far more fragile. The coup has also provided new business opportunities, with demand for weapons at its highest point in decades. The regime has therefore sought renewed commitments to the status quo from all three groups as a way to mitigate these risks.

The KIA also assembles its own version of the Type-81 in an area it controls along the Chinese border, which has allowed some of its brigades to provide rifles to new PDFs operating in Myanmar’s northwest.

Another important member of the FPNCC is the KIA, one of Myanmar’s oldest and most well-known groups. The KIA signed a written ceasefire agreement with the military junta in 1994 but the truce broke down in 2011, leading to significant fighting. The KIA also assembles its own version of the Type-81 in an area it controls along the Chinese border, which has allowed some of its brigades to provide rifles to new PDFs operating in Myanmar’s northwest. However, the KIA’s access to light weapons and other sophisticated equipment is more limited in comparison with the UWSA.

The FPNCC alliance also includes the Arakan Army (AA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). Before their membership in the FPNCC, these groups were part of the Northern Alliance led by the KIA. In 2018, the trio began to drift away from the KIA after the latter signalled its willingness to pursue a bilateral ceasefire with the military. Dissatisfied with the terms of the deal on offer from the military, in 2019 the three groups broke from the KIA to form the Brotherhood Alliance before waging a largescale offensive against government forces in northern Shan State. The AA, MNDAA, and TNLA have all since grown closer to the UWSA, relying on the Wa as their primary source of political and military support.

In contrast to the KIA, the decade before the coup saw the AA, MNDAA, and TNLA expand their territorial reach and military capacity. Rather than exploit the coup as an opportunity to escalate attacks on Myanmar’s armed forces, the Brotherhood groups have spent the last two years consolidating their hard-won gains under the cover of informal ceasefire. Still, the possibility of direct action by Brotherhood groups has — given their proven skill on the battlefield — remained a serious concern for the junta. Illustratively, between 2021 and 2022 the regime dedicated an estimated 25% of its total mobile strike force to Rakhine to deter the AA from launching a renewed offensive.

Although the Brotherhood Alliance has not waged coordinated offensives since the coup, nor formally aligned itself with the NUG, it has issued multiple statements condemning the junta for its actions. Brotherhood groups have also slowly increased covert support for certain PDF outfits operating on their flanks by providing training and a limited quantity of arms. In January 2023, the MNDAA, awash in cash and weapons but short on recruits, graduated the second batch of fighters assigned to its new brigade, the 611th. A new concept, the 611th Brigade is a multi-ethnic force comprised of PDF fighters from across the country who could not otherwise acquire proper training or weapons. The AA and TNLA have also helped train or equip new outfits, including PDFs linked to the NUG as well as other non-aligned groups.

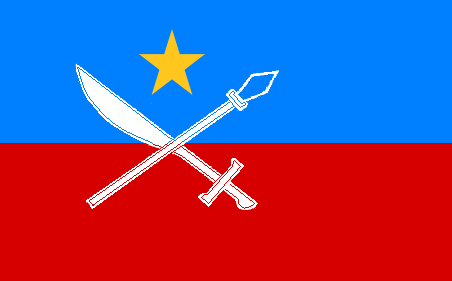

Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC) Operational Areas and Control Zones

China’s policy shift

Following two years of ambivalence, China abruptly shifted its stance in early 2023, pursuing its interests in ways that ultimately benefit the regime. Several factors likely influenced this shift. As others have noted, China maintains a number of geostrategic and economic interests in Myanmar, including a gas pipeline connecting Yunnan Province to the Andaman Sea. Following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions in China in January 2023, Chinese officials may have seen a need to ensure stability in the border area in order to safeguard their interests or kickstart stalled investment projects.

More importantly, however, Beijing appears to be driven by a concern that other actors are beginning to influence the course of events in Myanmar. In November 2022, news broke that the NUG would open an office in Washington, DC. The following month, the United States Congress authorised non-lethal assistance to Myanmar’s opposition through the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act. Sources with knowledge of his remarks say that Deng specifically told the FPNCC groups that China was unhappy to see the NUG officially open its Washington office on 13 February 2023.

Another possible source of China’s concern could come from the regime’s own messaging. On both Telegram and Twitter, pro-regime accounts frequently spread conspiracies about direct Western involvement on the ground. These claims often focus on the Free Burma Rangers (FBR), an evangelist paramilitary group which provides humanitarian relief and training to armed opposition groups and their supporters in areas near the Thai border. The FBR is run by David Eubank, a former US Army Special Forces and Ranger officer.

In February 2023, sources indicated that a number of Burmese-Americans who formerly served in the US armed forces were, in their capacity as private US citizens, providing training to PDFs in areas along the Thai border.

In February 2023, sources indicated that a number of Burmese-Americans who formerly served in the US armed forces were, in their capacity as private US citizens, providing training to PDFs in areas along the Thai border. That month, pro-NUG media reported that a special operations force unit operating in the KNU’s area of control was receiving training from ‘US Marines’. A month earlier, the MNDAA had publicised the graduation of the 611th Brigade’s second intake of recruits. The unit included fighters who had initially received training in areas near the Thai border but had then moved up toward the Chinese border in search of weapons.

Taken together, these developments may have given China the impression that some anti-junta forces operating near the Thai border were being increasingly influenced by the West. More importantly, some of these units had then begun to shift their operations towards China’s interests along its own border with Myanmar’s northeast. In a potential sign of this concern, sources say that China pressured the MNDAA to move its 611th Brigade further away from the border with Yunnan. However, not all agree that China is truly concerned about Western influence in Myanmar. As one diplomat based in the region stated, Beijing is using ‘an unfortunate series of unrelated events’ as a pretext to deepen its own involvement in the country.

New dealings

Members of the FPNCC gathered for an internal meeting at Panghsang, the UWSA’s headquarters, on 15 and 16 March 2023 before travelling to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, to hold a third round of talks with Deng. A statement released after the internal meeting made several revealing points. Firstly, the FPNCC welcomed China’s intervention in helping to solve Myanmar’s internal armed conflicts and promised to continue working with the Chinese government to ensure stability along the border. Given the context, the point appeared to affirm a willingness to uphold ceasefires with the junta by forgoing military action in the borderlands.

Secondly, the FPNCC’s press release mentioned the pursuit of a federal democratic union as a lasting solution to the conflict. Notably, the statement insisted that different ethnic groups must rely on themselves to achieve peace with the Bamar people, suggesting that the vision laid out by the NUG is not the only path towards peace based on a future federal arrangement.

Although the Brotherhood Alliance groups have insisted since the coup that they support the popular anti-military movement, on 1 June 2023 leaders from the bloc held an initial round of in-person negotiations with the regime at the NDAA’s headquarters at Mongla in Shan State

Although the Brotherhood Alliance groups have insisted since the coup that they support the popular anti-military movement, on 1 June 2023 leaders from the bloc held an initial round of in-person negotiations with the regime at the NDAA’s headquarters at Mongla in Shan State. Alliance leaders and their supporters attempted to de-emphasise the significance of the meeting by insisting that it was merely a consequence of China’s pressure, with the implication being that nothing would come of it.

While pressure from China has certainly encouraged dialogue, EAOs have their own reasons to bargain with the junta. On 14 May 2023, Cyclone Mocha devastated large portions of Rakhine State, where the AA operates. The destruction appears to have weakened the AA by destroying stockpiles important to its supporters, and by creating an acute humanitarian crisis. For the AA, this would be a bad time to resume fighting with the regime. More broadly, the current national crisis presents a rare opportunity for FPNCC groups to win concessions from the embattled regime without the need to fight. Except for the KIA, all members of the FPNCC have only become stronger under the cover of ceasefire, a dynamic which incentivises the further stabilisation of relations with the regime.

Given the current political environment and their own dislike for the junta, the Brotherhood groups are unlikely to strike any formal agreement at this time. However, the current talks offer the regime a chance to strengthen lines of communication and enhance the ongoing informal ceasefire, lowering the risk of serious fighting. From this perspective, simply getting the Brotherhood Alliance to the table was a major accomplishment, made possible in part by China.

How China’s diplomacy prolongs the junta’s lifespan

Backed by assurances from China, the regime’s talks with FPNCC members, however preliminary or vague, have for the first time since the coup given it the confidence to begin moving portions of strike forces out of Rakhine and Shan and to redeploy them to resistance hotspots in the Dry Zone, Kayah and Chin. Since February 2023, these units have taken part in escalated military offensives involving direct assaults on resistance stronghold areas. They have also carried out increasingly frequent atrocities and acts of extreme violence, including the rape, beheading, dismemberment and burning of resistance fighters and their supporters.

With resources stretched by the uprising of the past two years, the regime’s strategy has prioritised a hold over assets needed for long-term survival, rather than the near-term maintenance of control over the rural countryside or remote peripheries. This has included the defence of important bases, key logistic routes, weapons factories, economic centres and state institutions. So far, regime forces have managed to keep a relatively firm grip on these priorities. Given that a majority of the EAOs powerful enough to contest these core interests are now negotiating with the junta, this trend is likely to continue.

Unless they begin to receive substantially more military support from the EAOs or an unexpected external actor, resistance forces may struggle to physically capture or dismantle the regime’s key assets within the next several years.

China’s pressure on the FPNCC not to support the NUG’s PDFs will also make it harder for newer resistance forces to elevate their capabilities. Unless they begin to receive substantially more military support from the EAOs or an unexpected external actor, resistance forces may struggle to physically capture or dismantle the regime’s key assets within the next several years. While China cannot dissuade all arms transfers to the PDFs, even a partial reduction in EAO assistance will help slow the evolution of PDF capabilities, buying the junta time and the opportunity to increase pressure on its opponents and their civilian supporters.

By betting on its own stamina and high tolerance for instability, the junta aims to draw out the timeline of the conflict long enough to exhaust the PDFs and their supporters with punitive attacks and demoralising atrocities that require fewer resources to enact. In a little over two years since the coup, junta forces and their proxies have razed more than 70,000 homes across the country. These attacks, alongside fighting between combatants and other patterns of violence, have led to the displacement of nearly 1.6 million people since the coup, and they have left nearly a third of Myanmar’s population in need of humanitarian assistance. The regime’s ability to survive even two more years on the battlefield will probably result in a substantial increase to these figures.

Towards prolonged violence

By helping to moderate the threat posed by Myanmar’s most powerful EAOs, China’s support is likely to prolong the regime’s survivability on the battlefield. Without more direct involvement from Myanmar’s most powerful EAOs, no viable coalition will likely emerge to fundamentally challenge the regime’s core assets across all key fronts at once. Instead, China’s involvement helps the regime pursue its long-practiced strategy to divide and conquer.

This trajectory, however, should not be conflated with the regime’s ability to stamp out all forms of resistance. Under military rule, stabilising areas like the Dry Zone and southeast would take years, if not decades. In Kayah, for example, a renewed offensive initiated in March 2023 has borne only mixed results, despite the insertion of additional mobile units recently transferred from areas where FPNCC groups operate.

Overall, China’s behaviour in Myanmar looks mostly like an effort to secure its own interests, with support for the regime being an effect, rather than a driver of any policy. Yet signs are emerging that China could become blunter in the way it favours the regime. Although Chinese officials also instructed the junta not to wage offensives along their shared border, in early July 2023 junta forces did just that, launching an assault near the KIA’s nominal headquarters at a town called Laiza. In the last decade, the military has threatened Laiza several times as a way to force the KIA to negotiate. According to sources, China has been disappointed with the KIA’s attitudes towards its policies. It is possible that China tacitly approved the offensive to help the regime coerce the KIA into talks.

Importantly, however, China’s current policy appears primarily focused on areas near its border. Whether China will take issue with potential EAO campaigns in central Myanmar is unclear. In April 2023, junta forces launched an offensive against the Mandalay PDF, an outfit that has received significant support and battlefield leadership from the TNLA. The operation forced most of the PDF fighters to temporarily withdraw from the strategic area between Mandalay Region and Shan State and return to the TNLA’s stronghold. Junta forces could not pursue the retreating fighters, as that would risk a more direct confrontation with the TNLA and therefore jeopardise the current ceasefire.

Depending on the extent of its demands and ability to enforce them, China’s growing involvement could potentially incentivise EAOs to quietly wage low-intensity proxy war via the PDFs in Myanmar’s centre while maintaining ceasefires with the regime in the peripheries. If conflict endures throughout Myanmar’s interior, China could extend its reach by influencing which PDF units receive support. According to one source, China may have already funnelled a small number of weapons to a newer resistance unit that is not aligned with the NUG. In its current form, China’s intervention pushes Myanmar down a path toward prolonged instability and fragmentation, even as it secures its own border and interests inside the country.

Morgan Michaels is a Research Fellow for Southeast Asian Politics and Foreign Policy at the IISS. He leads the production and development of the Myanmar Conflict Map.

Website and graphics by freelance information designer Brody Smith.