How conflict dynamics in Myanmar are challenging state-centric humanitarianism

The ongoing humanitarian crisis is widespread but varies geographically, as humanitarian outcomes and responses depend on the varied ways in which the junta has targeted civilians, local capacities for delivering aid, and the presence of international borders.

Graphics by Brody Smith and Anton Dzeviatau

Multiple factors explain the international community’s humanitarian failure in Myanmar, including a general preoccupation with major conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. After Dr Noeleen Heyzer stepped down from her role as the UN Special Envoy on Myanmar in June 2023, the position remained vacant for ten months, perhaps reflecting Myanmar’s position in the Secretary-General’s list of priorities. But competing crises, limited political will and insufficient donor commitments are only part of the impediment to a more robust humanitarian response in Myanmar. Another problem is an incompatibility between the nature of the humanitarian crisis and the tools and mechanisms that the international community had deployed to address it.

Mainstream humanitarian institutions largely presume that states are part of the solution to a humanitarian crisis, rather than the source of it. Since the end of the Cold War, international humanitarian agencies have generally sought to strengthen state institutions, without addressing the role of state-building in exacerbating conflicts and disasters. Despite its patchy track record, this approach persists in part because it has allowed Western states — which remain by far the biggest funders of mainstream humanitarianism today — to maintain, albeit precariously, the moral and political authority they have sought. After all, international humanitarian interventions have largely been planned within Western foreign and defence ministries, and hence have been inseparable from Western governments’ strategic goals. In other words, mainstream humanitarianism operates on the presumption that global security is best served by supporting state institutions in places beset by civil war.

In Myanmar, the state itself has inflamed the humanitarian crisis and blocked responses to it as part of its campaign against opposition forces. In this context, statebuilding could stand at cross-purposes with humanitarian institutions’ pursuit of regional and global stability. Two factors further confound international responses to the humanitarian situation in Myanmar. Firstly, conflict dynamics vary geographically, as the Myanmar military has modulated the manner in which it targets civilians according to which armed opponents it is facing, as well as the presence — or lack thereof — of international borders in some warscapes. Secondly, the nature of the conflict in Myanmar makes it difficult for organisations to quantify the extent of the humanitarian crisis using aggregated, countrywide figures. Displacement figures and other humanitarian indicators vary dramatically depending on the context and the actor producing them.

Such complexity, however, does not necessarily preclude effective humanitarian responses. Across the country, local actors have demonstrated real capacity to mitigate the fallout of the ongoing war; among them resistance groups, grassroots organisations, and cross-border networks. Through private contributions, diaspora support, and some funding from international donors that have begun to rethink their approach to Myanmar, these actors have found ways to support conflict-affected populations outside the confines of mainstream humanitarianism.

Difficulties in enumerating Myanmar’s “humanitarian” crisis

The contemporary notion of humanitarianism, and the institutions that put it into practice, were created in response to refugee crises in Europe after the first and second world wars. Humanitarianism, initially conceived of as a means of protecting refugees, presupposed an opposite category — that of citizens, assumed to fall under the protection of states whose sovereignty international organisations and other states were not to infringe on. Since then, international institutions have been guided by a notion of humanitarianism that is supposed to be in harmony with state interests.

State-centric humanitarianism poses problems not only for addressing Myanmar’s humanitarian crisis but also for documenting it in the first place. Displacement figures are a mainstay of the UN’s emergency updates, yet they capture only part of the story. The number of internally displaced people is underreported in any context, because data collectors focus on people who have fled to relatively stable and accessible places, such as camps. This excludes ‘invisible’ internally displaced people, such as those living with relatives in dispersed locations or in monasteries and churches. Displacement counts can also exclude people who pre-emptively flee their homes in anticipation of violence or other dangers, especially if an armed event has not been recorded nearby.

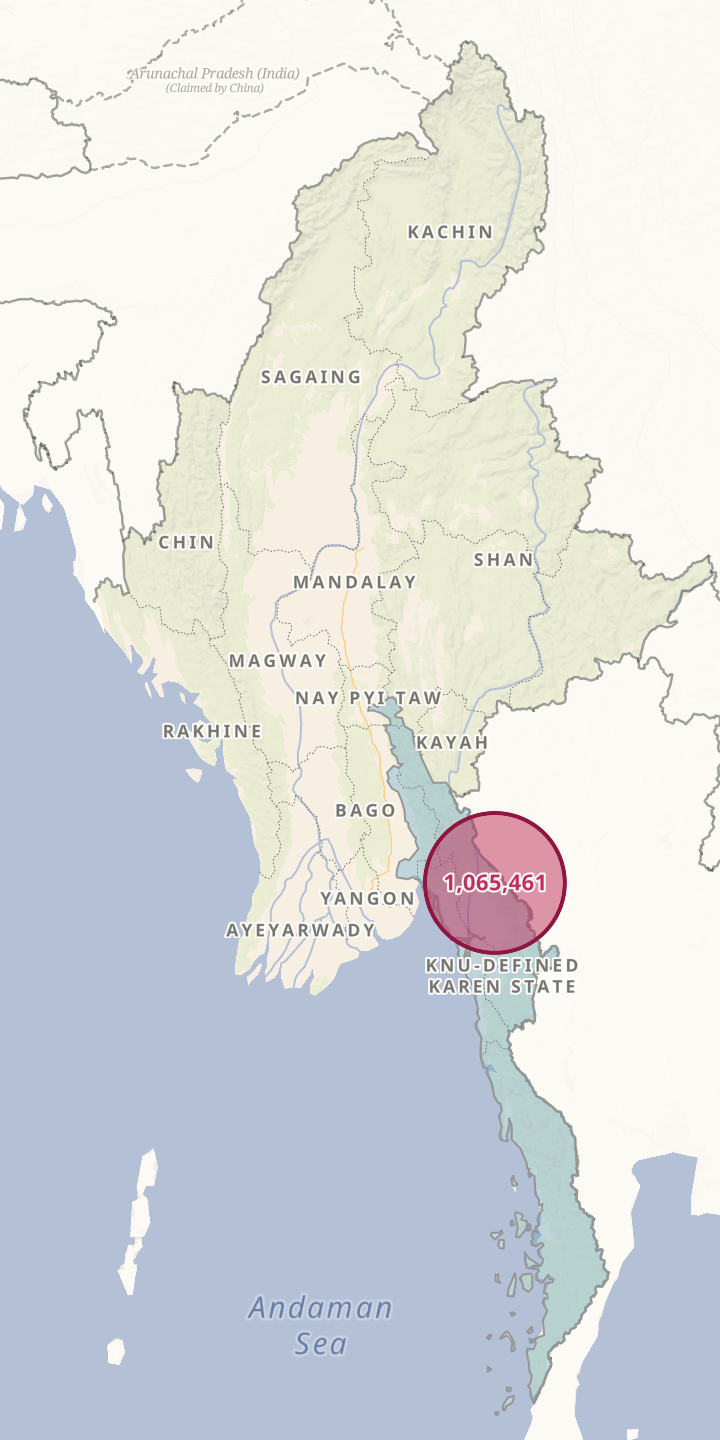

Yet the specific nature of the conflict in Myanmar — given its intensity, frequency and countrywide spread — has made it particularly difficult for international organisations to gather reliable or comprehensive data. While many conflict-affected areas are simply difficult to reach, primary data collection is often also intentionally obstructed by the State Administration Council’s (SAC) imposition of internet blackouts and the matrix of restrictions it puts on humanitarian actors. Checkpoints set up by the SAC or other armed actors can prevent local and international organisations from accessing the worst-affected areas to conduct needs assessments. This has led to wide variations in reporting. For example, the Karen National Union (KNU) reported in January 2024 that there were over 750,000 internally displaced people in southeast Myanmar, more than twice the UN’s estimate of 340,000 internally displaced people in the same area.

Issues around access and numerical discrepancies understandably cause misgivings among international actors seeking to intervene in Myanmar’s crisis. In the aftermath of scandals elsewhere, in the past two decades humanitarian agencies have become increasingly concerned with corruption, which in this context refers to the misuse of humanitarian aid for private gain. In conflict situations, the consequences of such corruption can be very severe. For example, using data from two dozen African countries, scholars have shown that the appropriation of monetary and in-kind assistance by predatory armed groups can exacerbate rent-seeking behaviours. In response, humanitarian actors have taken steps to ensure accountability and due diligence in the delivery of aid. Combined with a perception that states uphold order and act in the interests of citizens, concerns about corruption have resulted in a preference for aid delivered through state-sanctioned channels, the use of formal financial institutions, and the selection of registered organisations as local partners. These preferences are meant to ensure that humanitarian aid — often publicly funded by donor governments — is put to work impartially, neutrally and for a public purpose.

However, the Myanmar context challenges the assumption that the interests of the state and the interests of the public are aligned. The trajectory of the conflict so far — and indeed the history of the Myanmar military — shows that the military has predominantly worked to secure its own survival at the expense of large segments of the civilian population.

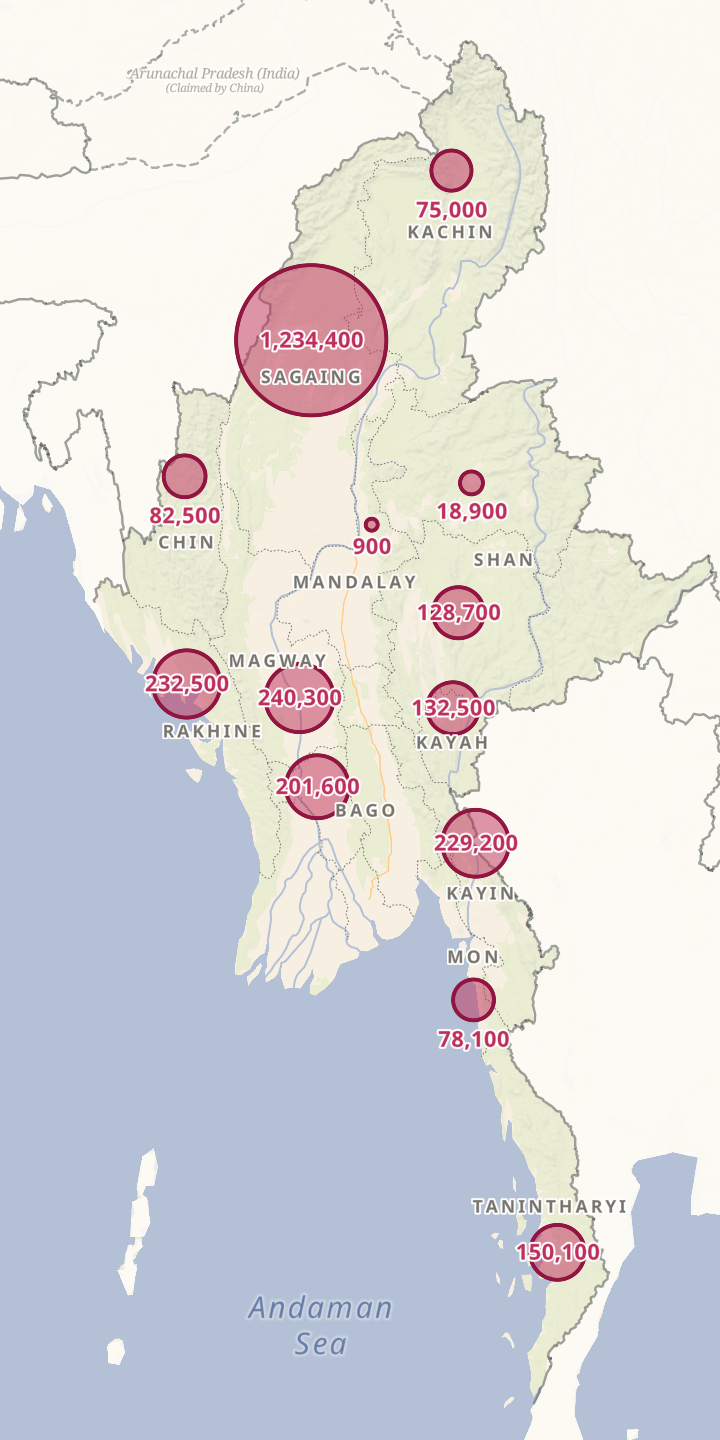

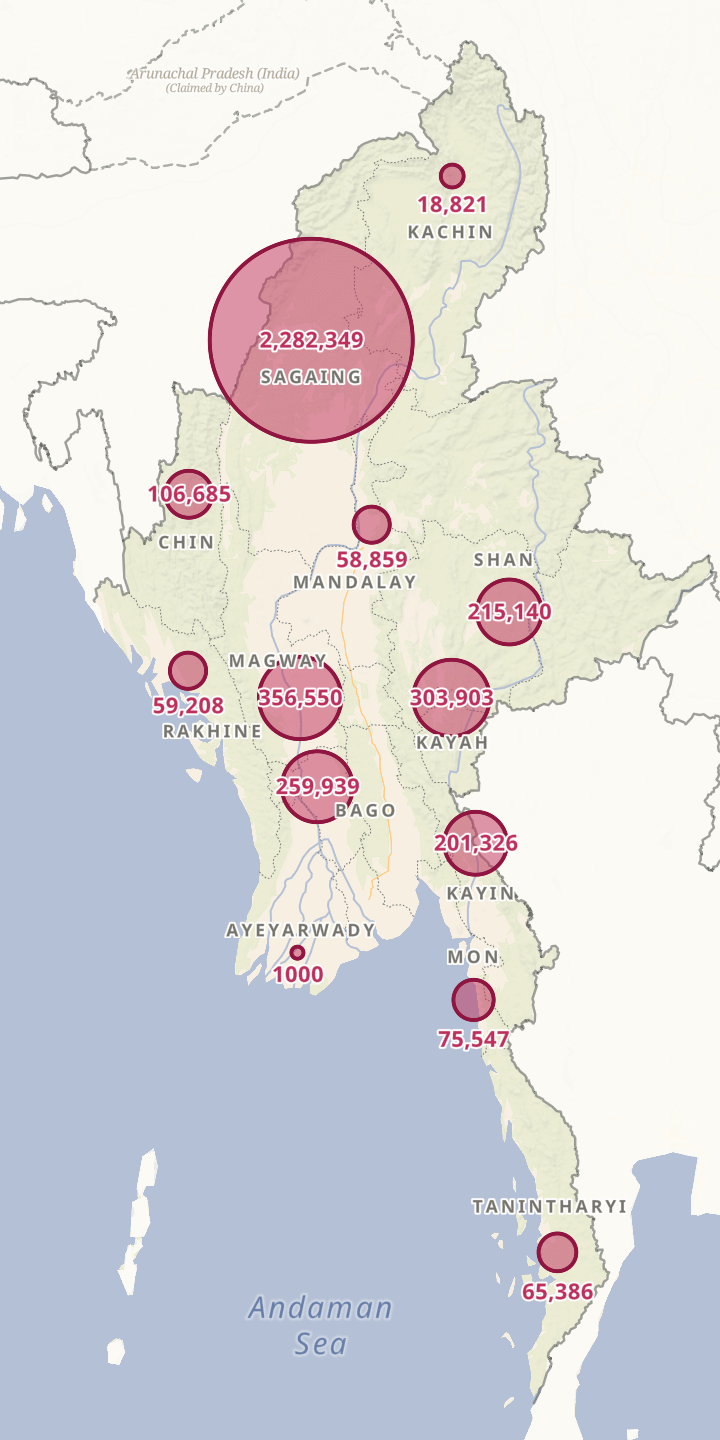

Refugee flows across borders by receiving country

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),June 2024

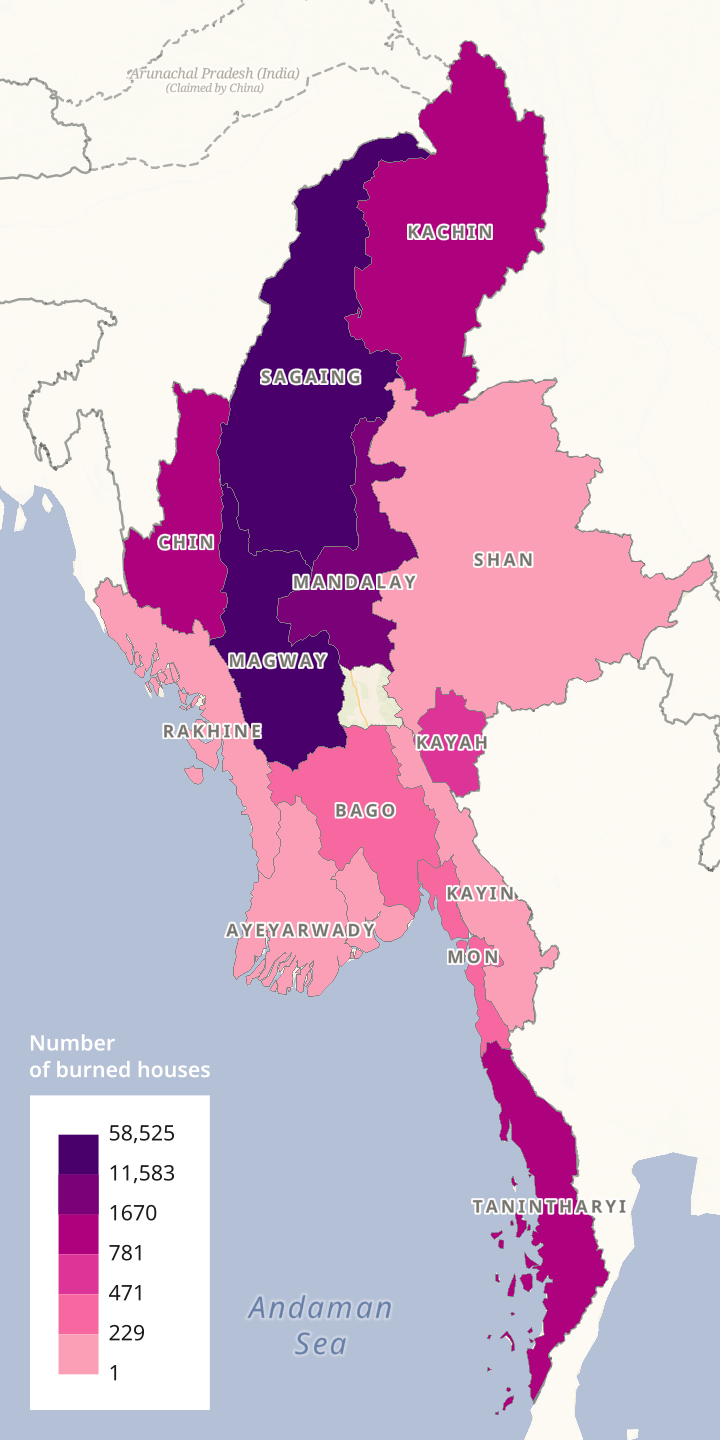

Source: Institute for Strategy and Policy,December 2023

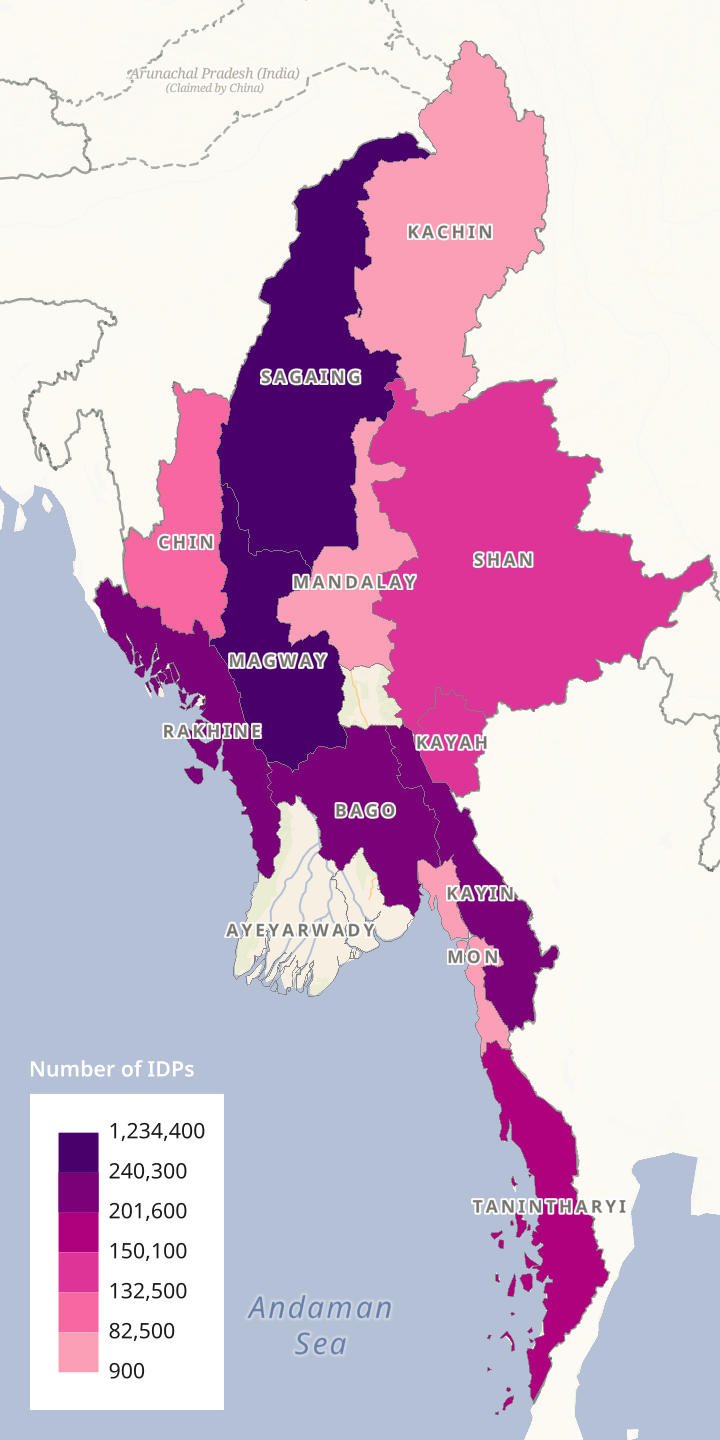

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) by state

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),June 2024

Source: Institute for Strategy and Policy (ISP),December 2023

Source: Committee for Internally DisplacedKaren People (CIDKP), April 2024

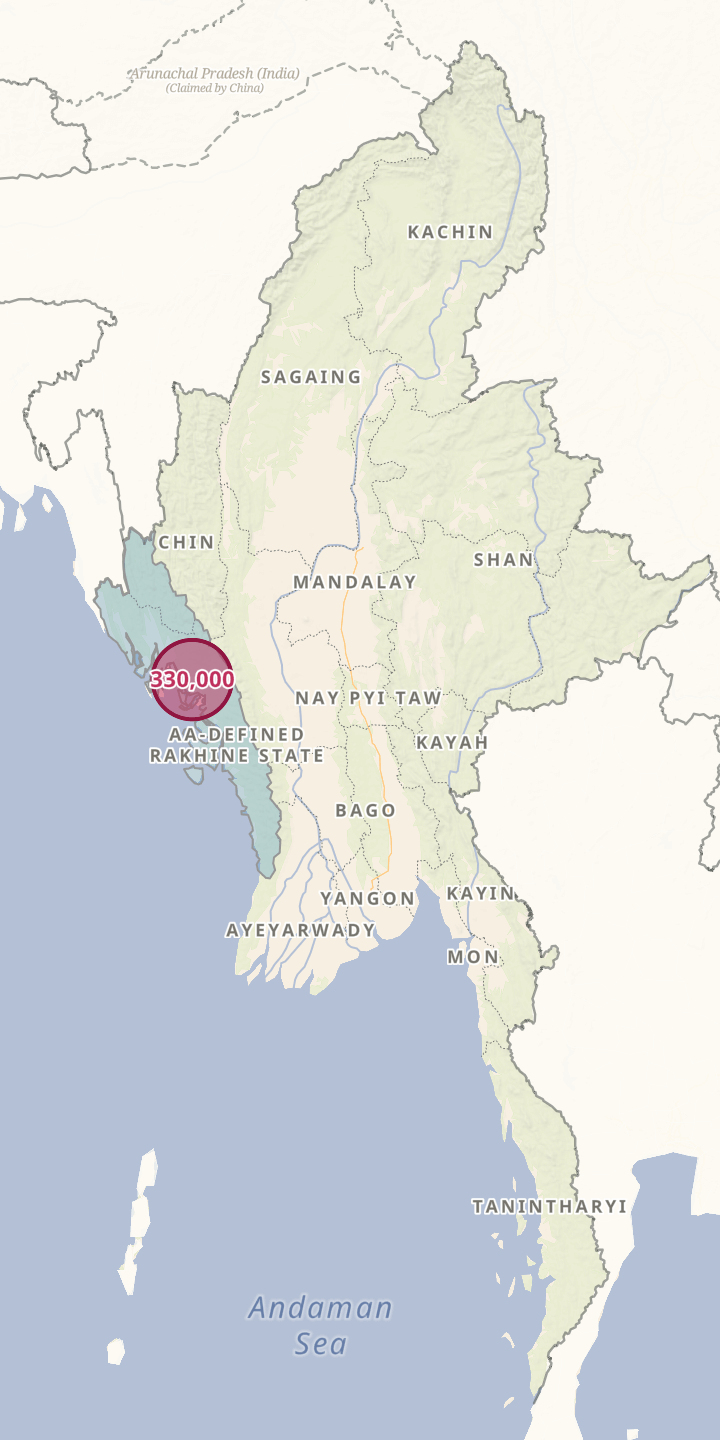

Source: United League of Arakan/Arakan Army(ULA/AA), February 2024

The geography of war and displacement

While armed violence has been recorded in 96% of Myanmar’s townships in the three years since the coup, conflict dynamics differ across the country, as armed violence alters local social, political and economic relations. For this reason the IISS has created a framework that divides post-coup Myanmar into six warscapes, illustrating how the war has played out unevenly across the country.

The warscapes framework can also be applied to help gain an understanding of humanitarian issues in Myanmar. While the Myanmar military has historically utilised collective punishment against the civilian population as a mainstay of its counterinsurgency strategy, the way it deploys armed violence against civilians varies across Myanmar depending on battlefield conditions and the types of armed groups it is fighting against. In the post-coup context, the SAC’s counter-insurgency campaigns against People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) have differed from its campaigns against ethnic armed organisations (EAOs). In the central Dry Zone, a predominantly Bamar-Buddhist area where PDFs largely fend for themselves in battle, SAC foot soldiers have intensively targeted the civilian population through a mass campaign of arson. In the borderlands where more powerful EAOs operate, the SAC’s use of arson is more limited. Instead, communities in EAO areas face other forms of collective punishment, such as blockades and indiscriminate shelling.

International borders also shape the humanitarian situation. Based on their stance towards the SAC, Myanmar’s neighbours decide to what extent they will tolerate refugee flows into their territory and the delivery of aid through it. Yet smaller-scale social dynamics also shape the cross-border movement of refugees and humanitarian aid too. On one hand, in India’s Mizoram, ethnic ties motivate communities to welcome Chin refugees despite a central government that often appears hostile towards those fleeing Myanmar; on the other hand, the China border is mostly closed to refugees, although those attempting to cross it have been re-routed to territories in Myanmar controlled by China-backed EAOs, a move that falls in step with Beijing’s concern that instability in Myanmar will compromise China’s border security. The interplay between these factors reflects the complex histories of Myanmar’s borderlands, in which the presence of armed groups, ethnic and religious ties, and formal and informal economic activities transcend the official boundaries that demarcate Myanmar’s territory.

Another factor creating different humanitarian situations across the warscapes is that of the local capacities for humanitarian response — and the extent to which those capacities are internationally recognised. The coup has aggravated a tension between international and local humanitarian responses. Besides the ‘gross underfunding’ of the UN’s humanitarian response to Myanmar, UN agencies also face travel restrictions imposed by the regime, which has refused to grant access to aid workers and blocked the transport of food and medicines. However, some observers have urged donors to look beyond internationally driven humanitarian responses, arguing that local networks of activists, civilians and religious groups have been more effective humanitarian actors than international organisations. Donors may overlook such local networks, however, because they are too ‘political’, given that they are often allied with the resistance movement or because they are assumed not to meet international standards. The extent to which local humanitarian networks have been established and the way they have been organised vary across Myanmar. For example, networks of local humanitarian and faith-based organisations operate in Kachin and Karen states, but have not been documented to the same extent in the Dry Zone. Nevertheless, in areas where the regime has a limited presence, they can make a vital contribution to attenuating the damage that the conflict has wrought.

Displacement in central Myanmar

The burning of homes and civilian infrastructure has contributed to soaring rates of internal displacement in areas far from Myanmar’s external borders. These arson campaigns are concentrated in the Dry Zone, particularly Sagaing region. In the first two years after the coup, Data for Myanmar reported that nearly 80% of the 55,000 homes that had burned down were in Sagaing. The UNOCHA reported no displacement in Sagaing before the coup; now, estimates of the number of internally displaced people there range from one million to over two million, more than in any other state or region.

Top 10 townships with the largest number of burned houses

Source: Data for Myanmar (D4M)

The number of burned houses by township compared with the number of Internally Displaced People (IDPs)

Burned houses

Source: Data for Myanmar (D4M),November 2023

IDPs

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),June 2024

Displacement in the Dry Zone is largely driven by the Myanmar military’s scorched-earth campaign against PDFs, formed to fight the incumbent regime. The regime has responded particularly violently towards PDFs, seeking not only to deter them from holding territory but also to damage their morale and deny them supporters and potential recruits. This strategy of ‘deliberate and wanton destruction’ has blurred the line between civilians and combatants, locking the humanitarian crisis and the escalation of the conflict in a destructive upward spiral. Since the coup, the regime’s targeting of civilians has driven them to take up arms, which in turn has led the regime to increase the severity of its crack-down on civilians deemed susceptible to the influence of resistance forces. Spectacular acts of brutality — what the political scientist Lee-Ann Fujii has called ‘violent displays’ — further aggravate this dynamic: there have been villages reduced to ash, and reports of the Dry Zone’s inhabitants encountering bodies charred and beheaded by the regime.

Taken together with the manner in which violence has occurred, the humanitarian crisis in the Dry Zone can be understood not as an after-effect of the conflict but as part of the regime’s strategy of draining PDFs of civilian support by breaking their will to resist. Although over the years the military has wielded this strategy — inaugurated six decades ago as the ‘four cuts’ counterinsurgency doctrine — against legion enemies, it has found its clearest and most brutal expression in the Dry Zone since the coup.

Although internal displacement is rife in the Dry Zone, it is difficult to get a fine-grained picture of the conditions that people face when they have fled from their homes. In part this is because people displaced by arson often do not live in camps, but instead in nearby villages, or in forests and farmland. This also means that the first people they seek help from are often other civilians, who are themselves pressed for money and food, and who worry that their own villages will be set ablaze. In one report, people displaced from a village in Magway were still displaced a year later. Despite initially finding work as farm labourers, the village’s former inhabitants had to stop working when the farmers who had hired them also fled. Experiences like this show how the humanitarian crisis in the Dry Zone has been alleviated by social ties, while also straining them as the war wears on. Even so, people have found ways of coping, pooling resources between households or pulling their children out of school to work in tea shops or as housemaids for wealthier families.

The difficulty of delivering aid to these areas is compounded by the SAC’s crackdown on humanitarian actors. In 2022 the regime imposed sweeping controls over civil society through the new Organisation Registration Law, effectively forcing registered organisations to ‘watch the war from the sidelines’. This has put humanitarian actors in a bind: register, and be subject to the SAC’s legal controls; or operate under the radar, and incur penalties for being an unlawful association. The regime’s scorched-earth treatment of resistance forces has made this legal minefield even tricker to navigate, for in order to reach displacement sites, local organisations must negotiate access with PDFs — which the regime considers to be ‘terrorists’. Although self-organised welfare groups, omnipresent in rural Myanmar, have been well positioned to offer humanitarian aid, they have been set back by the regime’s controls.

One factor that could mitigate the humanitarian situation in central Myanmar is the extent to which administrative structures established by resistance forces can become focal points for the delivery of aid. The National Unity Government (NUG) claims that its People’s Administrations have been established in 29 townships in Sagaing and in seven in Magway, while grassroots networks independent of the NUG have been established too: the Sagaing Forum, which convenes PDFs that remain unaligned with the shadow government, now claims to coordinate aid deliveries. Given the trajectory of the conflict, these efforts can be read not as deliberate attempts to fragment aid deliveries but as creative responses to an already fragmented landscape of control and coercion resulting from the regime’s severe crackdown on PDFs. NUG-allied People’s Administrations are decidedly not neutral — and are perceived as a threat by the SAC — but they are addressing the ongoing conflict in a way that humanitarian aid delivered through international mechanisms has not, albeit imperfectly and with limited resources.

Displacement across borders

Besides internal displacement, the conflict in Myanmar has also resulted in an influx of refugees into neighbouring countries. The Institute of Strategy and Policy — Myanmar (ISP) reported in late 2023 that more than one million refugees had fled from Myanmar since the coup. Adding to this the number of people who have left Myanmar because of the political and economic instability caused by years of fighting, the total could be several times higher. Even before the coup, millions had fled Myanmar for conflict-related reasons, although they were not considered refugees but rather migrants, most of whom had entered neighbouring countries without papers.

The word ‘refugee’ carries a specific meaning in international law, which originated in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. The definition of refugees according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) hinges on a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’ and a lack of ‘protection’ — terms that have long been contested in international law. This situation is compounded by the fact that the three neighbouring countries receiving refugees from Myanmar — Bangladesh, Thailand and India — are not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, although their central governments have, to varying degrees, allowed the UNHCR to establish a presence in those three countries. Furthermore, given the restrictions that receiving governments have placed on refugees — for example, restricting their ability to access employment or travel outside the local area — some have avoided registering as refugees, choosing instead to risk arrest and deportation while working in the informal sector.

The issue of refugees — defined broadly here as people who have crossed borders for reasons related to armed violence in Myanmar — is one way in which the ongoing conflict has shifted regional geopolitics. Yet the refugee issue is not only shaped by states, but also by cross-border ties among local communities.

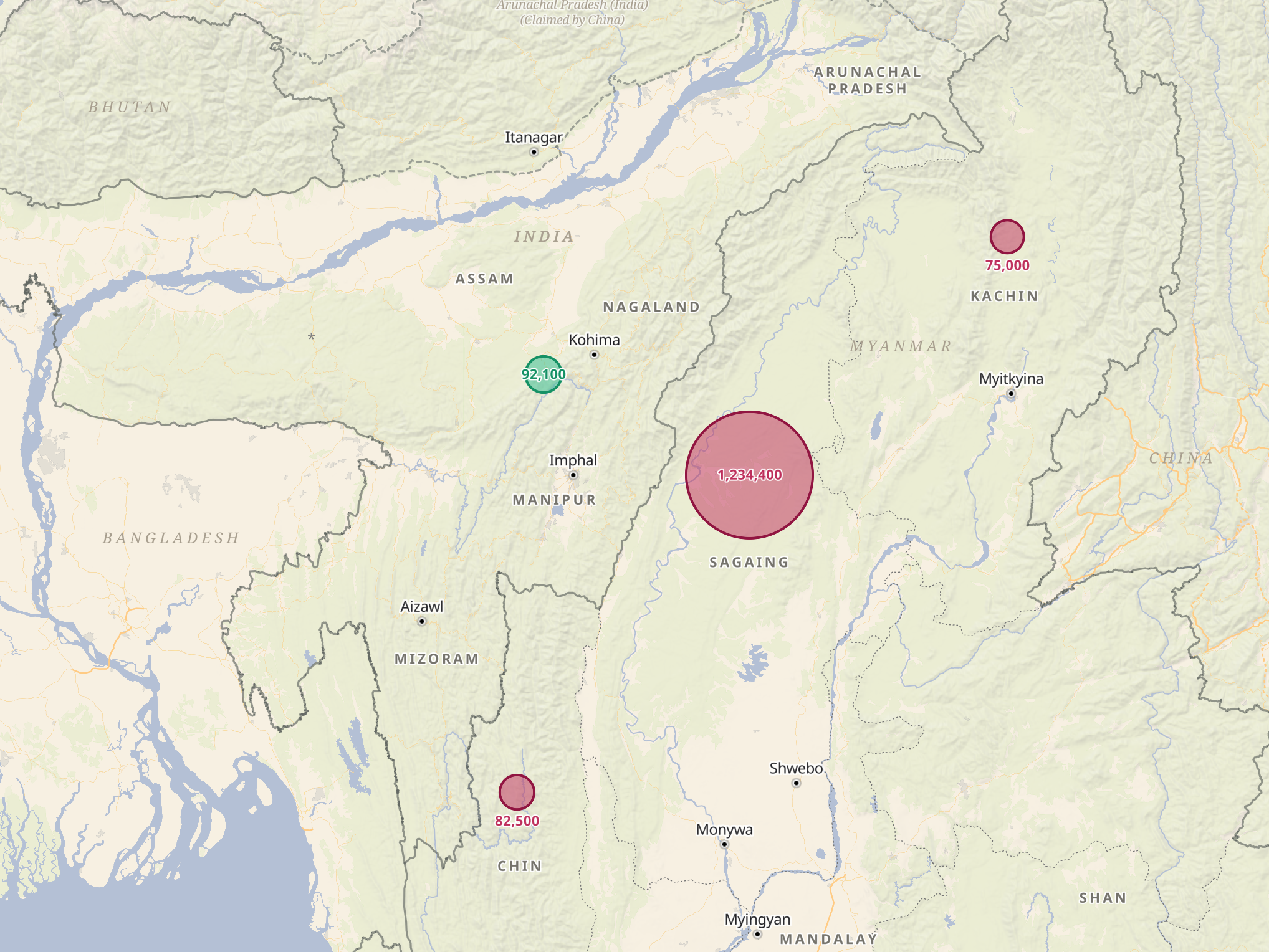

India clamps down on refugees from Myanmar

In January 2024, New Delhi announced that it would fence the more than 1,600-kilometre-long border between India and Myanmar. It cited a need to ensure the internal security of the country and to stem historic forms of ‘disorder’ in its northeast, which had resurfaced in the previous year. In May 2023, communal violence escalated in India’s Manipur, triggered by the granting of Scheduled Tribe status to Meiteis, who comprise half of Manipur’s population. This would allow Meiteis to secure reservation in government jobs and in educational institutions, and to access forest lands — potentially edging out other communities with Scheduled Tribe status in Manipur, namely Kukis and Nagas. These episodes of communal violence were intertwined with displacement from Myanmar: Kukis are related to Chin people in Myanmar. Allegedly, Meiteis worried that the arrival of Chin refugees would threaten the narrow demographic majority they enjoyed in Manipur.

Myanmar refugees in India and IDPs in the northwestern states of Myanmar

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), June 2024

For at least 74,000 refugees — mostly Chin — who have fled Myanmar for India and others who may have considered joining them, the proposed border fence will have serious implications. Of these, by the UNHCR’s count, 20,000 had arrived in India before the coup, although even then, other estimates of the number of Chin people in Mizoram alone surpassed that fivefold. Furthermore, the coup almost immediately triggered a further exodus of largely Chin people from Myanmar’s northwest to India’s northeast, especially Mizoram. By forming new armed groups and reactivating their ethnonational struggle, Chin people have been integral to the countrywide resistance against the regime and have been brutally punished by it as a result. After an arduous and dangerous journey to the border, Chin refugees were received on the Indian side by Mizos, with whom they share ethnic and kinship ties. Indeed, while Mizo–Chin relations have sometimes been strained, there has overall been a long history of affinity between them: the two groups share a common heritage and a Christian faith, both are considered ‘others’ in their respective nation states, and many from Mizoram had also sought safety among Chin in Myanmar in periods of bitter conflict. ‘There aren’t many Chin people who don’t have relatives in Mizoram,’ one Chin refugee told reporters — ‘almost every house [now] has guests.’ These ties have sustained Chin refugees in Mizoram, who the state government has granted entry into state schools despite New Delhi’s friendliness towards the SAC and its hostility towards new arrivals.

Although the US$3.7m border fence has yet to be erected, New Delhi has already sought to clamp down on the border by revoking a decades-old free-movement policy. Before 2024, flight across this border had been possible because citizens of India or Myanmar living close to the border were allowed to travel across it, up to sixteen kilometres inside the neighbouring country. The border had not only been ‘porous, but completely open.’ Furthermore, in the absence of the central government’s support, the arrival of Myanmar refugees has begun to fatigue some of India’s host communities. This is one reason why some local actors on the Indian side, although long circumspect towards New Delhi, have acquiesced to the Indian government’s moves to secure the border. New Delhi’s previous proposals to fence the India–Myanmar border had stalled amid objections by the Mizoram government and civil society, but more recently these local actors have been suggesting that refugee flows should at least be better managed, even if they hope to maintain the openness of the border. Worryingly, reports have also emerged of the deportation of Myanmar refugees, whose biometric data has been released to the junta. As a result of the ongoing conflict in Myanmar, centre-periphery relations on both sides of the border hang in the balance.

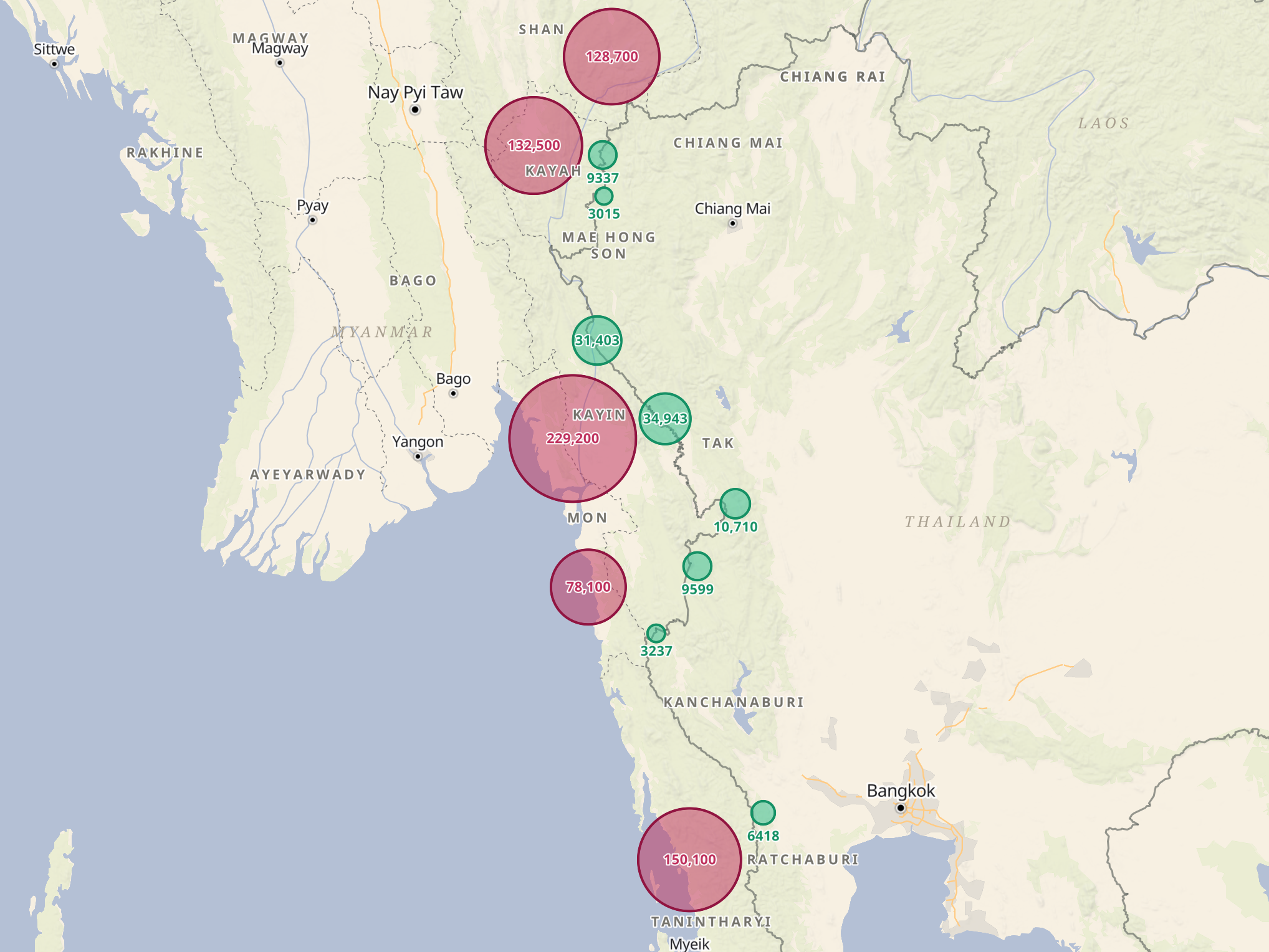

Refugees in Thailand caught in the geopolitics of aid

Grassroots organisations along the 2,400km border between Thailand and Myanmar are highly capable providers of humanitarian assistance, but as in India their effectiveness has been limited by the bilateral relationship. At least 45,000 people have fled from Myanmar to Thailand since the coup, joining 90,000 refugees from previous years who had been living in nine refugee camps along the border. Thailand also hosts a large population of migrants from Myanmar, approximately 20% of whom have arrived since the coup. The International Organization for Migration estimates the total number to be 1.5 million, although the true figure could be several times higher.

Myanmar refugees in Thai camps and IDPs in the southeastern states of Myanmar

The Border Consortium, July 2024

The history of displacement along the Thailand–Myanmar border has been shaped by a protracted conflict between the Karen National Union (KNU) and successive Myanmar governments, which began in 1949. In the late 1990s, in response to cross-border attacks on refugee settlements, the Thai government consolidated Karen refugees into larger camps — seven with a Karen majority and two with a Karenni majority, reflecting the two main ethnonational movements in southeast Myanmar. The Thai government has restricted the UNHCR’s role in these camps, inadvertently lending grassroots organisations and non-governmental organisations — most prominently the Border Consortium and its predecessors — greater autonomy over the day-to-day administration of the camps. The Karen Refugee Committee (KRC), for example, has become established in all seven ‘Karen’ camps, taking on more extensive and sophisticated roles in camp governance over time, and has continued to negotiate with the Thai government, NGOs and international organisation on behalf of refugees.

In the decade before the coup, however, the hopes vested by Western governments and international organisations in Myanmar’s ‘semi-democratic intermezzo’ caused them to reduce funding for the Karen and Karenni camps by more than 50%. Camp committees reported that refugees were receiving decreased rations but were still banned from leaving the camps to work, putting them in an impossible position. This, combined with refugees’ anxieties that they were being pressured to return to Myanmar, contributed to a spate of suicides in the camps. Moreover, this shift in donors’ attention impacted not only camp refugees but also those outside the camps, approximately half of whom had fled armed violence in Myanmar. Over the past 40 years, an informal but comprehensive social system, cobbled together by donors, NGOs, and community organisations, has allowed migrants in Thailand to access education, healthcare and other social services. With the KNU’s consent, some grassroots organisations based in Thai border provinces also travelled inside contested areas of Myanmar, providing humanitarian aid to conflict-affected people.

The Thai government, however, has not embraced local humanitarian organisations. Instead, after coming to office in August 2023, the Srettha Thavisin government developed a plan to create a humanitarian corridor between the two countries, through which food and medical supplies could be delivered by the Myanmar Red Cross Society. Since the 2021 coup, Thailand’s stout defence of engagement with the junta in ASEAN debates about the bloc’s response to the conflict had earned it a reputation as the junta’s closest ally in the region. As a result, other ASEAN member states had been sceptical of previous Thai initiatives. But at their annual retreat in Luang Prabang in January 2024, ASEAN foreign ministers endorsed the new government’s plan.

Some details of the humanitarian corridor remain unclear. The parties involved reportedly completed their first aid delivery in March 2024. In response, the KNU thanked the Thai government for aid packages ‘unexpectedly’ delivered to 20,000 people displaced into KNU-controlled areas — implying that parts of the organisation had not been consulted prior to the aid delivery — but also warned that a Myanmar Air Force fighter jet had flown over some aid-distribution areas the next day, causing those residing there to flee in fear. The KNU, which has so far taken the leading role in the EAOs’ fight against the junta, faces a dilemma because of the humanitarian corridor: reject junta-sanctioned aid, and the KNU could be accused of violating international law for interfering with humanitarian access; accept the aid, and it could be seen as reneging on its fight against the junta. Moreover, leaked documents have revealed close links between the junta and the Myanmar Red Cross Society. EAOs like the KNU harbour suspicions that the corridor will be used in the way that Myanmar regimes have traditionally used humanitarian assistance — as an inducement to EAOs to offer concessions.

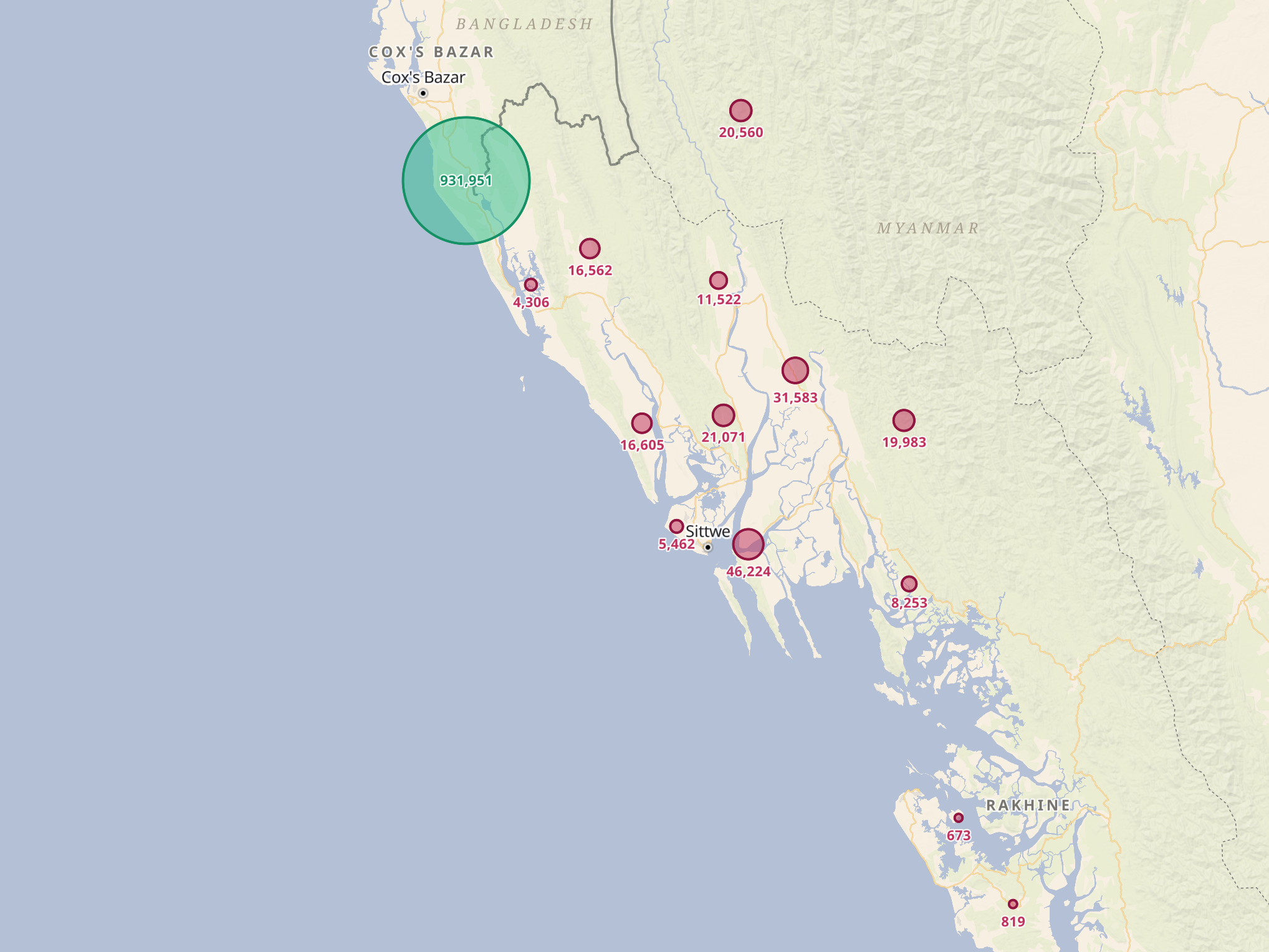

Growing insecurity for refugees in Bangladesh

The coup has left nearly one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, most of whom fled before 2021, with no good options. On one hand, the conflict in Myanmar has eliminated the possibility of return and citizenship for Rohingya in the short term, especially since the military that expelled Rohingya from Rakhine seven years ago is now in power. On the other hand, the scale of displacement across this border, and Dhaka’s unwillingness to integrate refugees into the local population, has resulted in Rohingya refugees facing intense overcrowding and spiralling violence in the camps. Kutupalong camp, which houses nearly 900,000 Rohingya refugees, is the largest refugee camp in the world.

Rohingya refugees in Bangladeshi camps and IDPs in townships of Rakhine and Paletwa

The IISS has documented how, since the mass exodus of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar seven years ago, the civil society groups that once flourished in the camps have been edged out by militant groups. This is because Dhaka, spooked by a rally in Kutupalong camp in 2019, at which 200,000 refugees called for Myanmar citizenship rights, has covertly propped up armed groups thought to support refugee repatriation ahead of citizenship. Initially, Bangladeshi security agencies were alleged to have supported the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), but they turned to other groups, including the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, after ARSA’s increasingly predatory behaviour earned the group international condemnation. This can be read as a cautionary tale about the consequences of suppressing civil-society activity: before 2021, the growth of non-violent activism in the camps was analogous to the situation on the Thailand—Myanmar border, where minority groups marginalised by the Myanmar government have found a space — however tenuous — from which they might advocate for themselves. However, on the Bangladesh—Myanmar border, the Bangladesh government’s foreclosure of this space — combined with the dwindling of aid into the camps — has escalated turf wars between armed groups, making life in the camps ever more violent and precarious.

In this context, conflict actors in Myanmar — notably the AA and the Myanmar military — have leveraged the Rohingya cause to edge out opposing conflict actors in Rakhine. A spate of battlefield victories this year has resulted in the AA taking control of most of Rakhine State’s northern half and its border with Bangladesh — including most of the areas where Rohingya live, if often in displacement sites. To complement the administrative institutions that the AA has built in the areas it controls, the AA had declared an intention to promote a unified identity among all ethnic and religious groups in Rakhine — including Rohingya. However, scholars remained cautious of the AA’s claims, stating that the AA’s Arakan Dream is still ‘undoubtedly primarily Rakhine-led’.

Recent events have made it look very unlikely that Rohingya will reap even marginal benefits from the AA’s battlefield successes. On one hand, in the face of extraordinary territorial losses, the regime has used coercion and inducement to recruit thousands of Rohingya across Rakhine State, including those displaced to closely surveilled detention camps, and in Bangladesh, where the regime is reportedly cooperating with Rohingya armed groups. Rohingya, who do not have Myanmar citizenship, face dire prospects in the military, where they are likely to be used as cannon fodder or as pawns for stoking inter-communal tensions. In April 2024, regime forces accompanied by Rohingya fighters reportedly razed hundreds of ethnic Rakhine homes in Buthidaung town, at the forefront of the fight between the military and the AA. On the other hand, the AA has retaliated against Rohingya for their alleged cooperation with the regime, declaring that Rohingya conscripts will be treated as part of the military and ‘attacked’. Weeks after the arson attacks in Buthidaung, AA fighters reportedly burned dozens of Rohingya villages and the Rohingya parts of the urban area, including locations where displaced Rohingya have sought shelter, causing thousands to flee.

In the escalating face-off between the regime and the AA in Rakhine, the Rohingya are caught between the two sides. Neither group offers them prospects for long-term settlement, let alone citizenship. Moreover, to advance their own interests, both sides have used Rohingya as tools for aggravating the very ethnic tensions that had made Rakhine State inhospitable for them in the first place.

Conclusion

Decades of human-rights documentation, field research and IISS analysis have firmly established how the Myanmar military’s campaigns against its opponents have targeted civilians, making clear how the military has been more focused on securing its survival than on protecting the population. In this context, traditional humanitarian responses that presuppose that the state is part of the solution are ill-suited to the task, given the state’s well-documented violence against nearly every segment of the population.

The mass displacement that has occurred in the Bamar Buddhist Dry Zone is not an offshoot of the conflict, but rather reflects the regime’s strategy of sowing fear among civilians so that they acquiesce to military rule. By contrast, civilians in Myanmar’s borderlands have largely been spared the spectacular arson campaigns that have destroyed Dry Zone villages since the coup, yet they have endured state violence over a far longer timescale, spanning decades. Although displacement dynamics vary geographically, these dynamics are driven by how the Myanmar military has responded to past and present threats to its rule, whether those threats come from newly formed armed groups or ethnoreligious minorities that are perceived as outsiders to the Bamar Buddhist polity.

The presence of international borders also shapes humanitarian outcomes. While cross-border ethnic and religious ties have allowed some Chin refugees to be welcomed in India, Rohingya are ensnared in a dire predicament as they face violence and precarity in both Bangladesh and Myanmar. And although grassroots institutions are emerging to tackle the humanitarian crisis across Myanmar, often with scant international recognition or support, these institutions are most effective along the Thailand—Myanmar border, where the nature of the border — which remained relatively unregulated until about 15 years ago — has facilitated innovative strategies to deliver aid into areas outside the state’s purview.

Myanmar’s humanitarian crisis cannot be solved by the state, and nor is it neatly circumscribed by the country’s borders. This is why some — including Hugo Slim, a scholar of humanitarianism, and Adelina Kamal, who formerly led the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance — have proposed that Myanmar’s people would be better served by a new type of aid architecture, involving ‘politically committed humanitarian action’ that supports local actors who simultaneously oppose the regime while circumventing its restrictions on the delivery of aid. Power dynamics affecting refugees on Myanmar’s borderlands show that the country’s humanitarian crisis is political in yet another way: refugees are ensnared in the domestic politics of neighbouring countries, which can move their central governments to leverage the humanitarian crisis as a means of extending their control over previously unregulated frontier areas or extracting rents in contested areas of Myanmar.

Ultimately, Myanmar’s humanitarian crisis is not a monolith. Just as the war is not a binary contest between the junta and the resistance, displacement is also shaped by various actors and the power relations between them, which vary across the country. Understanding Myanmar, according to one scholar, entails ‘checking our contemporary nation-state and ethno-racial baggage at the door’ — and the same can be said when it comes to formulating effective responses to the massive toll that the conflict has taken on the country’s people.

Dr Shona Loong is a senior scientist in political geography at the University of Zurich, and a non-resident Associate Fellow for Southeast Asian Politics and Foreign Policy at the IISS. Her research focuses on conflict, peacebuilding, and the politics of development in Myanmar and its borderlands.

Graphics by Brody Smith and Anton Dzeviatau.