Myanmar conflict update

Myanmar’s conflict intensifies as use of firepower expands

The Myanmar military is ramping up pressure on resistance forces and their civilian supporters with increasingly destructive displays of firepower. Violence is intensifying, and the humanitarian crisis is worsening.

By Morgan Michaels

Graphics by Brody Smith

Published May 2023

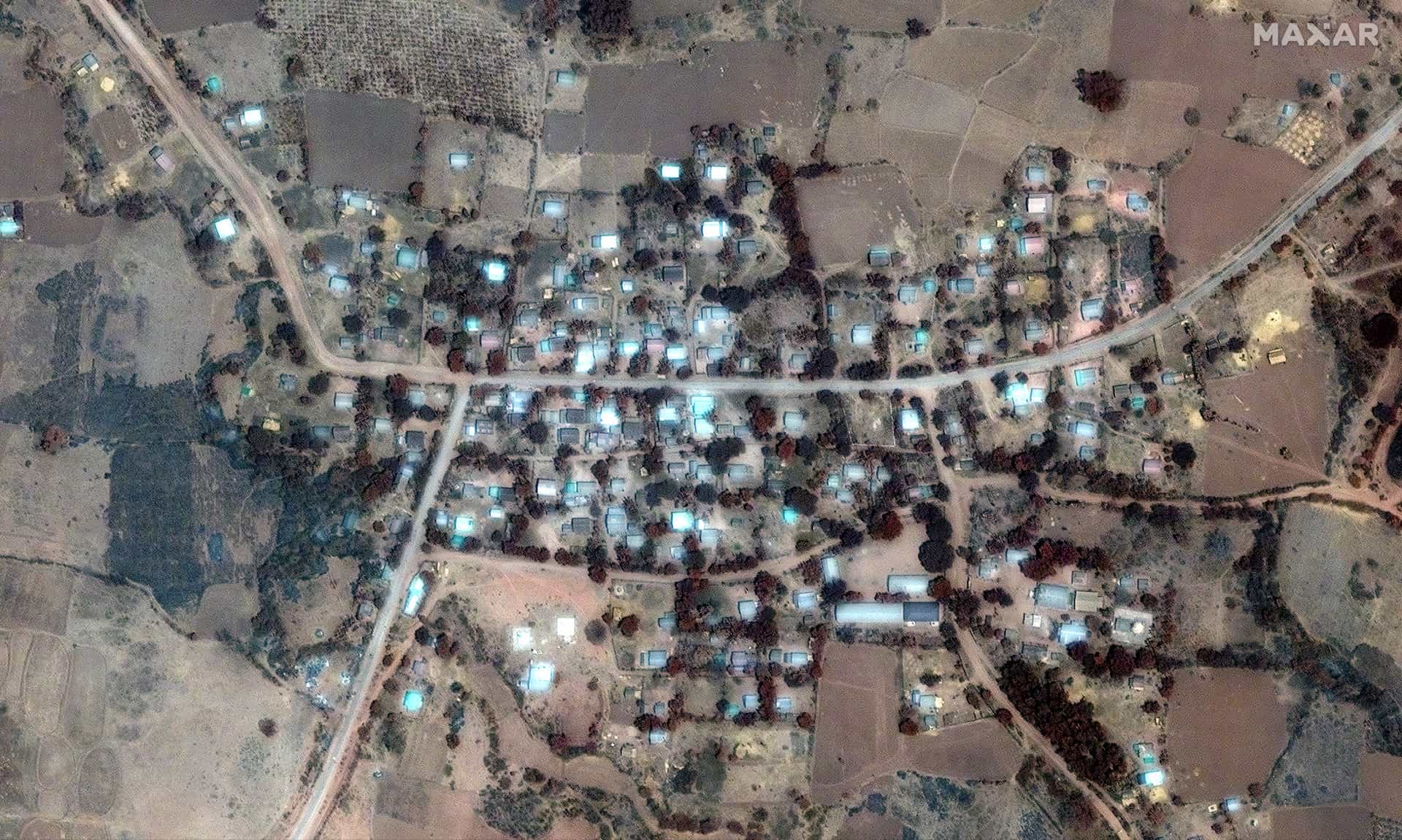

On 11 April 2023, a Myanmar Air Force jet dropped what were, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW), two thermobaric bombs on the opening ceremony of a People’s Administrative Team (PAT) office in Pa Zi Gyi, a remote village in Sagaing Region. The attack, which killed at least 130 adults and 40 children, is part of a trend involving the heightened use of aerial firepower against civilian and military targets. The Myanmar regime’s growing use of advanced weapons is driving a further intensification of violence and deepening of the post-coup crisis.

Since the outset of the conflict, the National Unity Government (NUG), established by lawmakers elected prior to the February 2021 coup, has worked to dismantle and replace the military regime’s administration with a structure overseen by the PATs. So far, local actors linked to the NUG claim to provide critical services in over half of the country’s 330 townships, a figure some say is indicative of the junta’s diminished control. In response, the regime has begun ramping up pressure on administrative targets and local-service providers with air and artillery strikes on medical clinics, schools, internally displaced persons (IDP) camps and PAT offices like the one destroyed at Pa Zi Gyi.

The regime’s escalating campaign is sustained by a steady supply of ordnance produced at home by the Directorate of Defence Industries, as well as by acquisitions of modern combat aircraft and helicopters from Russia and China. The high tempo of airstrikes, now a daily occurrence, is an indication of the regime’s capacity for maintenance, repair and overhaul. Precision strikes on clandestine jungle hideouts and remote offices like the one at Pa Zi Gyi also reflect the regime’s intelligence and targeting capabilities.

Across the Dry Zone, an asymmetry in firepower allows regime forces to penetrate or contest virtually any area, including those where its administration has been supplanted by opposition actors and local service providers. The PAT office in Pa Zi Gyi, which, according to HRW, also served some military purpose, was likely deemed secure given its location far from the main battle zone and other areas more firmly controlled by the regime.

The enormous display of firepower at Pa Zi Gyi, however, forced most of the surviving residents and local People’s Defence Force (PDF) fighters aligned with the NUG to flee, making it easier for two regime columns to approach the area on foot. On 20 April, soldiers raided the village before calling in additional air and artillery strikes, leading to the destruction of numerous houses. Fearful of future attacks or left without a home, most residents of Pa Zi Gyi and its surrounding villages remain displaced.

Aided by an expanding network of firebases and assets for close air support, regime forces in the Dry Zone are regularly able to push out PDF fighters from their villages and encampments. Even so, the regime lacks the numbers to occupy cleared territory, provide the necessary security to re-install its administration, or prevent resistance fighters from returning. To compensate for its weak force posture, the junta has largely relied on a mass campaign of arson, but this has not produced the desired results. A revised strategy appears to entail the increasing use of mass atrocities and displays of violence designed to crush the population’s will to resist or support alternative forms of governance in the first place.

During a raid on a village in Sagaing Township on 1 May, for example, regime soldiers reportedly captured and killed three men. One of them, a PDF leader, was disembowelled and beheaded as a warning to the village. On 10 May, soldiers raided the village of Nyaung Pin Thar in Bago Region, where they reportedly murdered 19 people, including four children, and burned their bodies. Regime-perpetrated massacres like these have become common across central areas where PDFs operate.

Where the more powerful ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) are involved, resistance fighters possess a greater ability than their counterparts in the Dry Zone to defend against attack and slow the junta’s advances. But this has not necessarily translated into better outcomes for civilians. At least 22 civilians were massacred outside a monastery in the opening days of a multi-pronged offensive against ethnic Karenni forces allied to the PDF. Although the offensive has struggled to maintain its momentum in the face of spirited resistance, it is likely that most of the population in Kayah State is now displaced and seeking shelter at makeshift camps, several of which the junta has bombed.

The sheer volume of firepower available to the regime enables it to exert tremendous pressure on resistance forces and their civilian supporters. Although Myanmar’s internal wars have historically been waged primarily with small arms and other light weapons, more capable munitions are increasingly defining the conflict landscape. This dynamic, especially when combined with patterns of collective punishment carried out by foot soldiers, is pushing the humanitarian crisis to new levels.

Given its strategy of exhausting local populations suspected of supporting the NUG, the military junta has thwarted the delivery of international aid to areas most in need. On 7 May, unidentified gunmen shot at a convoy of ASEAN officials on their way to visit IDPs receiving aid from the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance, in what some in the diplomatic community believe may have been a false-flag attack staged by the regime to discourage aid delivery. Three days later, the NUG and three EAO allies proposed a new mechanism to coordinate international aid. The statement was the first time since the crisis began that the NUG publicly mentioned the possibility of ceasefire for humanitarian reasons.