Methodology

The Myanmar Conflict Map is based on ongoing reports of violent incidents that have occurred in Myanmar since 1 July 2020, as collected in the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). ACLED collects data on a weekly basis from international and local media, including Burmese and ethnic media sources, then reviews it to ensure validity, accuracy and relevance. The IISS research team reviews ACLED’s data and adapts it to the Myanmar context. These adaptations take into account uncertainty around reporting on conflict in Myanmar, particularly with regard to details such as casualties and precise locations where incidents occurred. The site’s dashboard presently contains 33,634 violent events.

MAPPING CONFLICT INCIDENTS

The Myanmar Conflict Map takes into account three different degrees of spatial precision in its data. As in the ACLED codebook, Level 1 denotes an event for which precise geospatial information is available, such as the town or village where an event took place. Level 2 denotes cases where only an approximate event location was reported by open sources. In the Myanmar context, events that happened either between two villages or somewhere within a given township are frequently categorised as Level 2. Events reported only at the township level are usually coded to the main town, unless other identifying information is provided, such as proximity to a natural feature. ACLED ascribes Level 3 to events in the rare instances where media reports have cited only the state or region where they took place, in which case the coordinates for the capital city are used. Of the events listed on the Myanmar Conflict Map, 50.8% are Level 1 while 49.0% are Level 2.

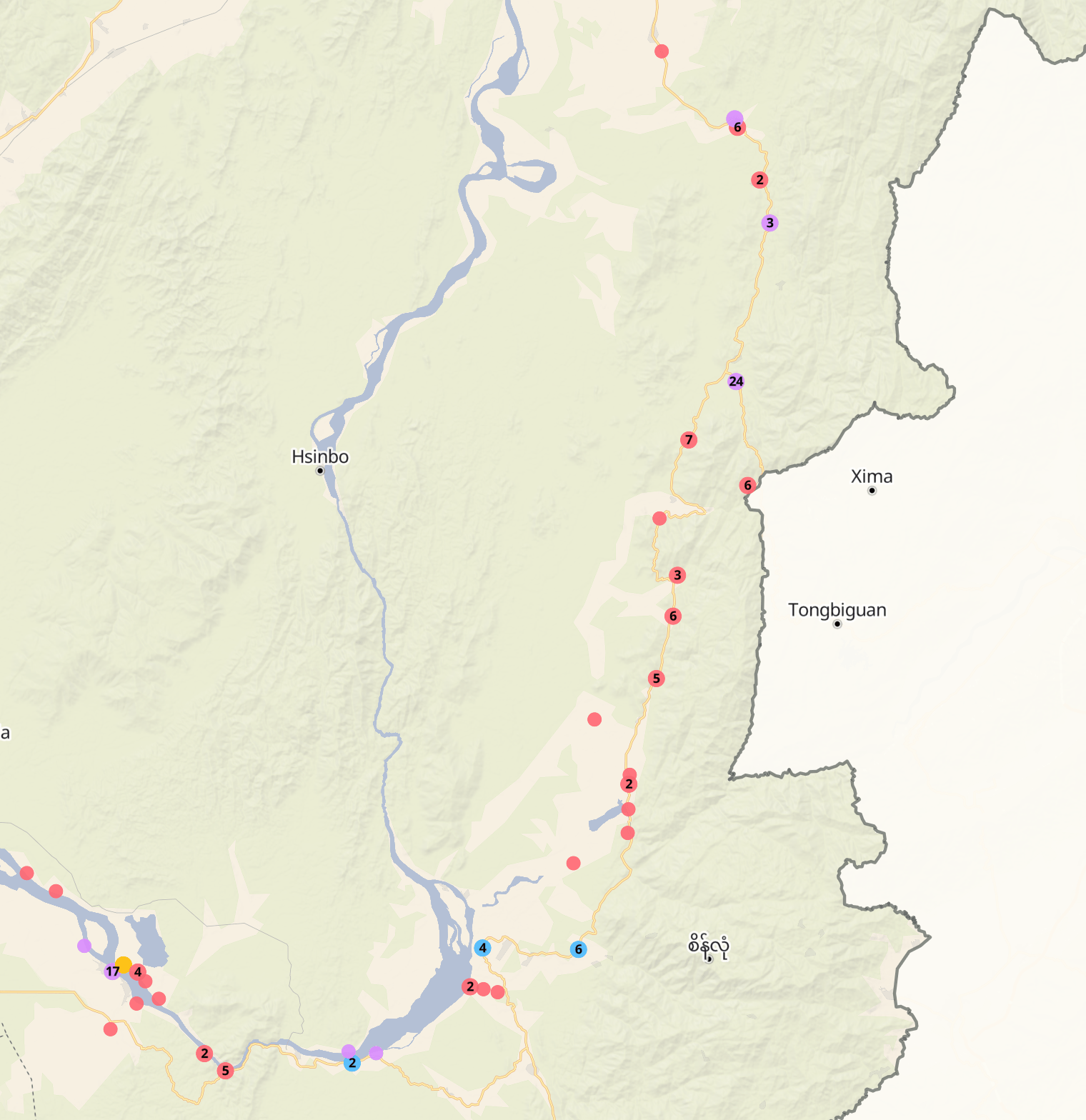

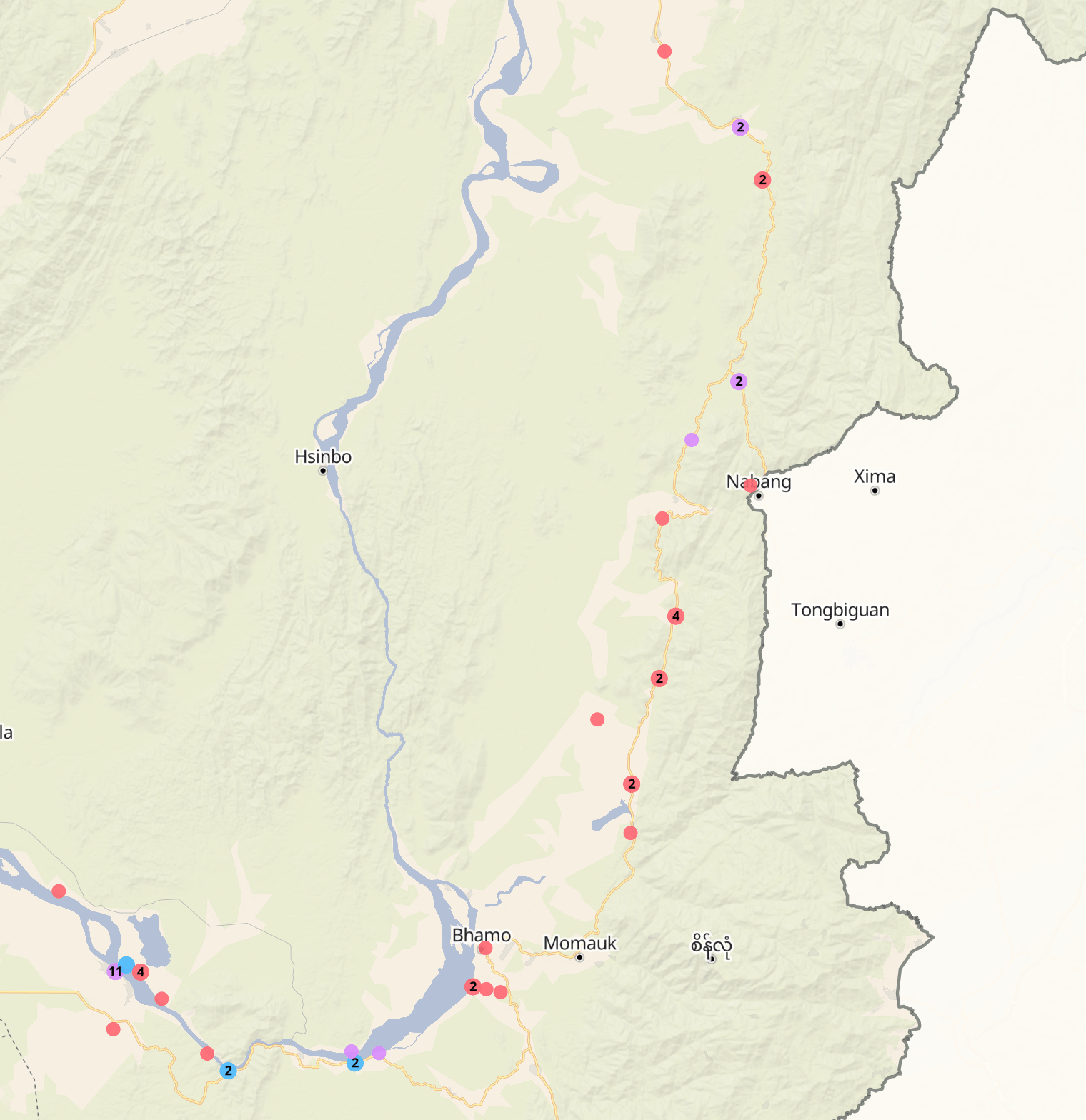

Recognising these uncertainties, the Myanmar Conflict Map employs two forms of spatial visualisation. The site’s main dashboard allocates each event a randomised geolocation within the township in which it occurred. The dashboard thus captures the prevalence and frequency of armed violence at the township level but cannot illustrate, for example, violent events occurring in specific villages or along specific roads. Meanwhile, maps featured in the Myanmar Conflict Updates that include ACLED data plot events according to the actual coordinates coded by ACLED, be they Level 1 or 2. As the map below shows, this method captures the general geospatial pattern of conflict episodes, which the IISS corroborates using other qualitative reports, including those provided by our sources.

Classifying incidents

ACLED categorises events into six types and 25 subtypes, which the research team reclassified into five event types to fit the Myanmar context:

- Attack/armed clash

- Remote explosives/improvised explosive devices

- Air/drone strike

- Crackdowns

- Infrastructure destruction

For example, the Myanmar Conflict Map uses ‘crackdowns’ to encompass the ACLED event subtypes ‘protests with intervention’, ‘violent demonstration’, ‘mob violence’ and ‘excessive force against protesters’. In the Myanmar context, the terms ‘violent demonstration’ and ‘mob violence’ can be misleading, given that events in these subtypes refer to attacks by regime security forces on protesters, sometimes using live ammunition, and protesters’ occasional use of tear gas, barricades and rudimentary weapons to defend themselves. These events have been recoded as ‘crackdowns’ to reflect the asymmetry of violence between the regime and civilians.

The Conflict Map excludes ACLED data in two instances: where the events in question were non-violent, and when events in a particular subtype are likely to have been significantly underreported. In particular, sexual violence and threats of sexual violence are widespread but vastly underreported. The research team has acknowledged the prevalence of sexual violence in its warscape series.

Recoding actors

As of July 2023, ACLED counted more than 1,500 distinct actors in Myanmar’s conflict during the preceding 12-month period. The research team classifies actors into four categories: ‘SAC forces’, ‘anti-SAC forces’, ‘ethnic armed organisations (EAOs)’, and ‘civilians’. Identification of ‘SAC’ and ‘anti-SAC’ forces was completed with the aid of local and international media reports, as well as by cross-referencing the social-media accounts of armed actors when possible.

In general, the IISS classifies as an EAO any armed actor that articulates ethnic rights or issues as central to its political cause. However, definitions of the term vary based on different political perspectives. During the peace process between 2011 and 2021, for example, the Myanmar military used the term EAO only for those groups it was willing to recognise as dialogue partners. In the post-coup era, some EAOs have begun to describe themselves as ‘ethnic resistance organisations’. The IISS continues to use the term EAO because of its recognisability among international audiences, but acknowledges variations in the ways these groups are defined.

The term EAO does not always indicate that groups are fighting against the regime. For example, the IISS classifies the Shanni Nationalities Army (SNA) as an EAO. Though it was previously non-aligned, following the 2021 coup the SNA openly sided with the SAC to fight against the Kachin Independence Army, another EAO. There are also EAOs that have been integrated into the Myanmar armed forces’ command as People’s Militia Forces, like the Pa‑O National Army. Some EAOs’ stances towards the SAC have shifted along the course of the conflict and continue to do so.

UNATTRIBUTED VIOLENCE

Between 1 July 2020 and 30 April 2024, the ACLED dataset recorded 4,684 events in which an ‘unidentified armed group’ was involved. This corresponded to 13.9% of all events in the dataset. The unidentified armed group in question was classified as ‘SAC’ or ‘anti-SAC’ if they had attacked anti-SAC or SAC targets respectively. However, this was not possible in most cases. For instance, ACLED data records landmine explosions, bomb blasts in teashops and abductions that are unclaimed by any actor. The ‘unattributed violence’ tab makes visible the spatial distribution of these known unknowns.

294 Townships

Conflict cartography and its limits

The Myanmar Conflict Map strives for the best possible cartographic representation of armed violence in the country since the coup. In adapting ACLED’s data to the Myanmar context, the IISS sought to ensure that the vocabulary in the map speaks to ongoing policy debates about Myanmar, and that the map reflects the asymmetrical conflict involving the SAC, anti-SAC forces and EAOs. The research team also recognises the dangers that journalists and their sources currently face, and the SAC’s use of communications blackouts as a counter-insurgency strategy. Actors on all sides of the conflict have an incentive to control information, and there remain many incidences of armed violence that, although reported on social media, are impossible for international and local media outlets to verify.

These contribute to a significant incidence of unattributed and possibly unreported violent events. By rendering these unattributed events visible, the map recognises that the conflict in Myanmar is a struggle over information as much as over territory, resources and rights. The accompanying commentary series complements the map by addressing unreported violence and other forms of violence that do not lend themselves to cartographic representation.